Fundamentals I wish you knew: bits and bytes. Part 2.

Here’s a file. It contains a series of integer values, stored as binary. I’d like you to do some processing of each value. How would you do it?

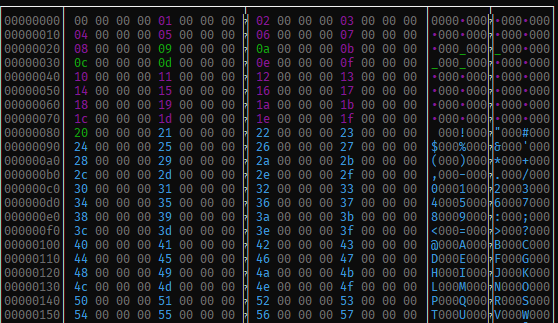

You decide to inspect the file contents:

> cat .\nums.bin

… and you see something like this get spit back at you on the command-line:

Hmm. Not too helpful. So…what now? If you’ve been programming for a while, you’re probably going to rub your hands together, fire up your favorite hex editor / viewer and verify what we’re actually dealing with here. Then you will probably start coding a solution.

If you’re one of an alarming number of recent computer science grads, you may be more likely to break out into a cold sweat. If accomplishing the task is tied to something important, like, say, doing well on a programming interview, you might start to panic a bit.

In a previous post I discussed the experience of interviewing multiple bright young computer science majors who struggled to write a program to work with simple binary data.

Specifically, we discussed a recurring pattern where the candidate does not understand that “32-bit integers” stored as “binary data” in a file will require them to read the actual byte values that make up those integers.

Text files. That’s what the kids know how to read, to the point they conclude that a file containing ‘32-bit’ integers must mean the data is a textual sequences of 32 ‘1’ and ‘0’ characters.

We cringe. Yet they seem not to know any better.

I should be clear that such candidates are not the majority; just, that there are enough of them now that it has the appearance of a trend.

Initially exasperating, I’ve come to a state of understanding: it seems to be the case that we are not reinforcing the most essential knowledge of how computers work, at least for a not-entirely-trivial portion of students.

Bits and bytes. They are fundamental.

What I would prefer you knew

If you are interviewing with me, what I hope you know are these basics:

- You know what bits are.

- You know what bytes are.

- You know your basic powers of two.

- You understand how hexadecimal works.

- If I give you a binary, hexadecimal or decimal number you can find a way to convert from one to the other.

- You understand the basics of how computer memory works.

- You understand what a file is.

- You have an idea of the difference between a ‘text’ file and a ‘binary’ file.

- If you had to read bytes from a file, or write bytes to a file, you would know how to do it conceptually.

Those are the basics.

When I ask my usual interview question, I go out of my way to tell the candidate that I want them to think about how they would solve the problem from a practical standpoint. Meaning: if I actually gave them a computer and a couple of files to process and told them I just needed the answer by the end of the day: how would they actually solve the problem? I’m not interested in a protracted discussion about theoretical algorithmic complexity accompanied by proofs. Yes, yes, I know you studied all that stuff to death in college. I know it’s useful. Here, however, we are talking about actual programming to solve a problem, not theory.

I mentioned being able to convert between the three most common bases (base 2, base 16, base 10) that we use as programmers. Do I require that you be able to do these conversions lightning fast in your head under pressure? No! I’m terrible at arithmetic; I couldn’t do that. I just care that you have some concept of how to go from, say, 0x222E0 to it’s decimal equivalent (140,000). Using a calculator is fine. Using a programming language is fine. The point is that when working with computers we very often need to convert between representations using actual data: numbers. Bytes. Individual bit patterns (i.e., flags and masks.)

Similarly I called out the need to have a conceptual idea of how to read from files or write to files. I never particularly care if you remember exactly how the API works: language or platform specific details can always be looked up in a reference. The idea, the concept, though…you should be able to sketch out what such an API might look like. Know what a buffer is. Know the concept of a stream interface. Be able to articulate how you might know when you’ve read to the end of a file. These are basic concepts I wish you knew.

Bonus knowledge

Some years back it would have been pretty unthinkable that graduating seniors who had studied computer science would not know this stuff completely cold. The world has changed.

Here is the bonus stuff, which while still quite fundamental is not quite as essential:

- Endianness

- Signed vs. unsigned values (Two’s complement)

- Encodings: ASCII, UTF8, UTF16

- Floating point

If you don’t have much knowledge of the above now, believe me, you will after a few years writing real-world code. Better to get some familiarity sooner rather than later.

Conclusion

I covered what I consider some really fundamental, bare-minimum concepts I really wish you knew before interviewing for a programming job. This knowledge will complement the really crucial skills I’m looking for:

- Critical thinking.

- Problem solving.

- Creativity

- Tenacity.

If you have the fundamentals, we can speak the same language. I can explain that I’m asking you to process a disk file that is just a sequence of integers.

I will probably even show you exactly what the raw data looks like: