The tragedy of ToList()

What do you see when you come across code like this?

docList.OrderByDescending(item => item.Score).ToList().ForEach(item =>

{

// Do something with item.

});

I see a tragic pit of failure for the ignorant, or callous indifference from those who should know better.

Either way, let’s discuss.

A bit of context

C programmers think memory management is too important to be left to the computer. LISP programmers think memory management is too important to be left to the user.

– Ellis and Stroustrup, The Annotated C++ Reference Manual

Automatic garbage collection (GC) in programming languages is a beautiful thing. It frees the programmer to focus on the essence of the problem they are trying to solve, not the minutiae of how the computer hardware actually implements the solution. This is especially true when applying functional programming techniques, where the declarative style of such programs makes how the computation is achieved unimportant compared to what it is achieving.

Newer programmers may have an incorrect impression that GC is a new, modern technique, designed to reduce the longstanding burden of manual memory management imposed by classical languages such as C and C++. This is entirely untrue, of course, as anyone who has studied computing history will know: one of the very first high-level programming languages, predating C by more than a decade, was John McCarthy’s LISP, a functional language that introduced the technique of garbage collection to the world. This was circa 1959, at the dawn of computing, a date so long ago that the modern generation can likely hardly fathom it.

GC makes a bargain with the programmer: leave the memory management to me, at the cost of losing complete control over every aspect of how your program is executed, including things like when memory is freed. This, consequently, means accepting some possible performance overhead and inefficiency in exchange for increased simplicity and correctness. Memory safety and correctness issues are historically one of the greatest sources of bugs in computer software, so in a very large percentage of cases this is a highly acceptable tradeoff.

Even in the world of systems programming, where the mere thought of GC is anathema to the extreme performance requirements and low level control needed in something like your operating system kernel, there is a push towards memory-safe languages like Rust. In a famous tweet, Mark Russinovich declared that we should consider traditional languages like C/C++ deprecated for new projects.

.NET developers have the luxury of working in an ecosystem that is memory safe by default via an excellent Garbage Collector implementation, while also providing escape hatches (unsafe, Span<T>, etc.) to allow optimization in paths where the overhead of GC might be unacceptable.

GC Quick Summary

The actual implementation of GC in .NET is a fairly complex topic; there are a lot of details related to different GC modes, various types of heaps, dealing with fragmentation and large objects, etc. I recommend reading the GC Documentation for details.

We can, however, summarize a few salient points:

- The vast majority of the types you define are likely to be classes and, thus, require GC.

- Application pauses and high CPU are some of the main performance issues in systems using garbage collection.

- The more garbage a program generates, the more work the GC has to do.

GC Abuse

It’s not the garbage collector that’s ruining your process. The garbage is ruining your process!

– Bryan Cantrill, Is It Time to Rewrite the Operating System in Rust?

The code snippet I opened this article with is tragic because it seems at first glance to so many programmers to be entirely reasonable. In fact, this kind of code is very common in my experience. This is even true in codebases where performance is critically important. Imagine a web service attempting to process hundreds or thousands of requests per-second, with minimal latency, filled with code like that.

In the minds of many programmers, more code means slower performance, less code means faster performance. Therefore, one-liners are superior! After all, how much code are we actually executing if it all fits on a single line?

These few innocuous tokens in a single line of code must be almost free, right?

ToList().ForEach(/* ... */)

Nothing could be further from the truth. The tragedy of ToList is that it seems so small, so innocent, a little flourish in the middle of a chain of calls to get us to the next item in the chain.

The issue, of course, is not about calling ToList() in and of itself. There are many reasons to take a sequence of things and turn them into a concrete list. Perhaps we want to perform a binary search, so we need the ability to access specific elements by index. Perhaps we need to make defensive copies before handing those copies to other threads, to avoid thread-safety issues. Perhaps we have a method that only accepts an IList<T> so we need to accommodate it. Or, perhaps we have an expensive LINQ query that we want to ensure only executes exactly once. These and many more possible scenarios are completely acceptable reasons to turn our sequence into a List.

However, that is not what we have in that code snippet.

Consider what the above code does for a moment. It allocates a List for the sole purpose of calling the ForEach method, because that method only exists on the concrete List<T> type. That’s right; unlike what you may have thought, the ForEach method is not part of the IEnumerable type (via LINQ), but is a one-off method defined on List<T>.

To be blunt, that ForEeach method offends the senses. It should not exist.

Why? Because it offers no advantage over simply using a traditional foreach loop, other than being able to make it a satisfying ‘fluent’ one-liner. Which leads to many developers calling ToList solely for the purpose of calling the ForEach method!

For those of us who care about avoiding completely needless, excessive garbage on the managed heap, this is indeed a tragic misuse of an otherwise fine and upstanding method.

Think about it. We have some (potentially large) sequence of data in memory. It is most likely already backed in memory by some sort of data structure, such as a List, an Array, a HashSet, etc. Yet because we want to call the ForEach method, we make an entire copy of that data in memory, on the managed heap. Copying the array costs time, it costs CPU and it creates a bunch of additional work for the GC. All of this could be avoided by just doing the simple thing and writing a traditional foreach loop.

var orderedList = docList.OrderByDescending(item => item.Score);

foreach (var item in orderedList)

{

// Do something with item.

}

Here we have the sane version of this kind of code; no unnecessary copying of the entire list in memory, just a plain old-fashioned foreach loop.

Many developers wonder why LINQ does not provide a ForEach method. The answer is that it violates the philosophy of the functional nature of LINQ, which discourages side effects in favor of an input sequence always producing some result as output. The result can be another sequence or it can be a discrete value, but it always produces some output. In contrast, the ForEach method produces no output value at all; it is only about side effects.

Finally, if you are so enamored with one-liners and method chaining that you cannot live without the silly ForEach method, you can always trivially implement your own:

internal static class IEnumerableExtensions

{

internal static void ForEach<T>(this IEnumerable<T> items, Action<T> action)

{

foreach (var item in items)

{

action(item);

}

}

}

At least that way you can avoid allocating unnecessary lists willy-nilly throughout your code.

Does ToList always allocate though?

Consider the following piece of code:

List<int> myList = [1, 2, 3, 4]

var result = AddFirstTwo(myList);

Console.WriteLine(result);

int AddFirstTwo(IEnumerable<int> values)

{

var list = values.ToList();

return list[0] + list[1];

}

While the AddFirstTwo method accepts any IEnumerable<int>, in this case the underlying type backing the IEnumerable is already a List! Isn’t the ToList method smart enough to notice this and simply return the underlying list without allocating any memory at all?

This is an unfortunate misconception that I have seen many developers voice. The answer is no, not at all.

ToList must by definition make a new list from the underlying data. That is part of its implicit contract. The method itself is described as:

Creates a List

from an IEnumerable .

Note the use of the word ‘Creates’. The method by definition always creates a new list, requiring that the contents are copied into that list from the underlying source. Any other behavior would break all sorts of code that relies on a copy being made, such as the defensive copying for thread safety scenario I mentioned earlier.

The same logic applies to ToArray as well.

Non-pessimization

Casey Muratori (known for his work in game engine design and optimization) did an excellent presentation some time back called Refterm Lecture Part 1 - Philosophies of Optimization that I highly recommend watching.

(I’ve mentioned this talk before, in my post on Fake Optimization)

I cite this talk often when I give presentations to other developers, as it introduced me to one of my now-favorite programming concepts: non-pessimization.

The idea is to avoid writing ‘pessimized’ code, where we can think of ‘pessimization’ as the opposite of ‘optimization’; that is, going out of your way to write code that makes the computer do more work than necessary, for no good reason whatsoever.

Calling ToList().ForEach() is a perfect example of pessimization in action.

Practice non-pessimization instead. Your garbage collector, and your users, will thank you.

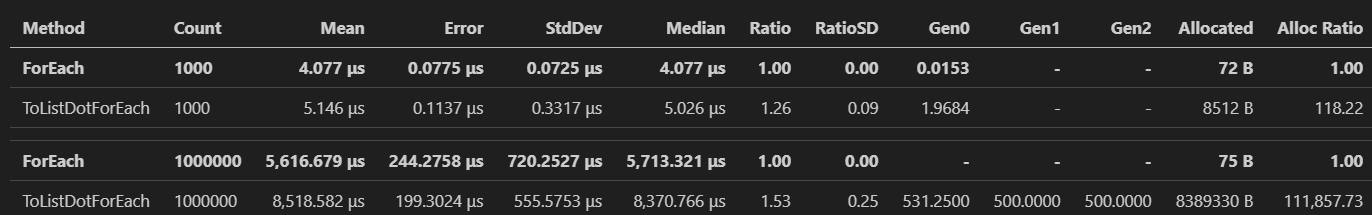

Here is a very simple benchmark showing the difference between using a traditional foreach loop and calling ToList().ForEach() instead:

Take particular note of the memory allocation ratio and think about the impact on the garbage collector.

Finding low hanging fruit using regular expressions

When I explore a codebase for the first time I must admit that one of the first things I do now is simply grep for ToList and see what pops up.

In fact, I have a magic regex that just finds bad code for me. (Should this be a Roslyn code analyzer instead of just a simple regex over the text of the source code? Probably!)

My preferred code search tool is ripgrep from the CLI, so my simple little technique is just this handy PowerShell function:

function bad

{

rg -i "\.(?:ToList|ToArray)\(\)\.(?!As|Json|Node\b|Index|CopyTo|FindLastIndex|AreMore)|Select\(. => .\)|(?:ToList|ToArray)\(\)\.Count > 0" --pcre2 --glob !*test* --glob !*Test* --glob *.cs $args[0]

}

What this attempts to flag, among other things, is the pattern of including a call to ToList() or ToArray() in the middle of a chain of other calls. Very often this means we are allocating a list and then throwing it away, doing nothing of value except creating additional garbage for the GC to have to deal with.

I present the following real-world example I came across recently, which the above regex called out as suspicious:

return groupedItemsDictionary.ToList().Select(x => new ItemView { Id = x.Key, Data = x.Value }).ToList();

Did the sensible programmer in you immediately recoil, or did this code look normal to you?

ToList().Select().ToList() is an anti-pattern. Any such use should immediately jump out as wrong.

Here are some more clear anti-patterns found in actual production code, and an example of how they could be re-written to be less offensive.

Bad 😔

var result = items.Select(d => d.Key).ToList().Contains(p.Id);

Better 😎

var result = items.Select(d => d.Key).Contains(p.Id);

Again, don’t inject ToList in the middle of a method chain for no reason. What purpose does it serve other than to create garbage?

Bad 😔

if (items?.Where(_ => _ != null && _.Id == indexId).ToArray().Length > 0)

Better 😎

if (items?.Where(x => x != null && x.Id == indexId).Any())

The original code for this last one really is quite terrible. Any time you see either ToList().Length > 0 or ToArray().Length > 0 or someEnumerable.Count() > 0 you immediately have to wonder why the Any() method was not used instead. Any requires only looking if there are any elements at all. The others require traversing the entire list.

(As a minor style point, using the discard character _ for an actual variable name is also a rather awful choice for readability.)

You may see variants of this anti-pattern, like this one:

if (items?.Where(x => x != null && x.Id == indexId).Count() > 0)

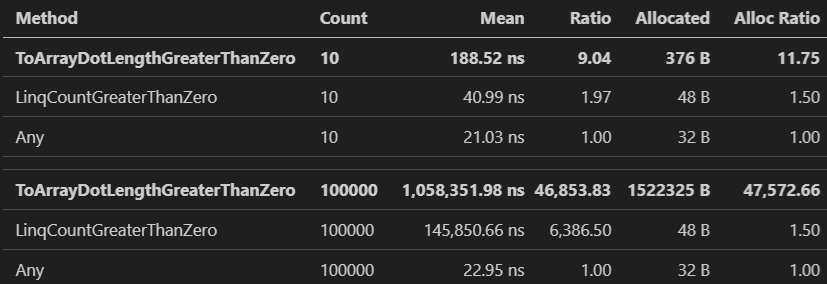

Just on the off chance you were not yet convinced that this kind of code should be terminated with extreme prejudice, here is a benchmark of the above scenario.

The results speak for themselves:

Again, not just in terms of potentially much higher latency (47,000 times slower for the large list!) but also in terms of memory usage (again, in this case, 47,000 times more memory for the GC to have to eventually clean up).

Case study - select the first five keys and return them as a list

Let’s examine another concrete example of a call that my “find bad code” regex flagged, once again in some code I was working in not that long ago:

List<KeyValuePair<string, int>> topicsList = topics.ToList();

topicsList.RemoveAll(item => item.Key == null);

topicsList.Sort((pair1, pair2) => pair2.Value.CompareTo(pair1.Value));

int numOfTopics = topicsList.Count;

List<string> sortedTopics = topicsList.Select(item => item.Key).ToList().GetRange(0, Math.Min(numOfTopics, 5));

return sortedTopics;

Examine this code for a moment. What do you think? Would you call this out in a code review?

Let’s say that you do, commenting “This code seems inefficient. Do we really need to make a copy of the entire list here before returning?”

You get the reply: “The interface contract requires that we return a List<T> here, so we don’t have a choice.”

Your response?

This code is an instructive microcosm of many similar small programming problems that come up in our day-to-day work all the time. We can distill the interesting part of this code (the part that calls ToList) into the following problem statement:

Given a List<T> of KeyValuePair<string, int>, take the first five items and return their keys as a List<string>.

We will simplify by assuming the list in question has at least five elements, so we can eliminate having to worry about Math.Min for the sake of this discussion.

This seems like a quite simple programming problem and, honestly, it is!

However, not all solutions are created equal.

Let’s briefly sketch out five approaches to solving this:

Approach #1 - Select, ToList, GetRange

return _keyValuePairs.Select(item => item.Key).ToList().GetRange(0, 5);

This is the approach we flagged in the original code review.

Approach #2 - GetRange, Select, ToList

return _keyValuePairs.GetRange(0, 5).Select(item => item.Key).ToList();

Approach #3 - Select, Take, ToList

return _keyValuePairs.Select(item => item.Key).Take(5).ToList();

Approach #4 - Take, Select, ToList

return _keyValuePairs.Take(5).Select(item => item.Key).ToList();

Approach #5 - Create a list, Write a loop

var result = new List<string>(5);

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++)

{

result.Add(_keyValuePairs[i].Key);

}

return result;

(Not a one-liner! 👀)

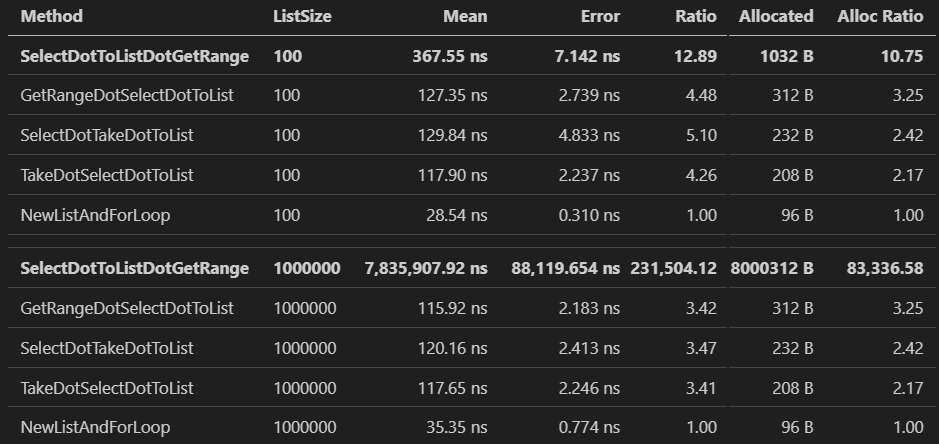

Results

I would say that tells the tale.

The original answer our hypothetical developer defended in their code review is unfathomably bad compared to the alternatives. The execution time is exponentially worse and has similarly terrible allocation numbers, meaning once again that choosing the wrong approach can easily create a massive amount of extra work for the GC.

Looking at these results and putting just a little bit of thought into them, it’s not hard to understand why the original code is so bad. Calling ToList() immediately materializes the entire list into memory. So even though we have a lazily evaluated LINQ statement (the Select), that does us no good if the next call is to ToList(), which will copy the entire sequence into a new list in memory.

Again, this is the tragedy of such a simple, innocuous seeming method call. A distracted or inexperienced developer can easily look at this code and think “looks good!” without realizing the performance landmine lurking behind it.

The LINQ variants naturally benefit from lazy evaluation / deferred execution. The LINQ query is always known to limit the results to at most five entries before it is ever executed, so we never need to pay the expense of evaluating more than five items, even if the list is a million items long.

If you’re paying attention you might ask: why is approach #2 allocating so much more memory than approaches #3, #4 and #5? Ask yourself: how many lists does that approach allocate? How many do the others allocate?

This is the kind of thing you need to condition yourself to think about when writing any kind of code that calls ToList or similar methods. Consider what is going on behind the scenes and ask yourself if this might lead to excessive memory allocations or other performance issues.

Finally, we get to see that sometimes the old ways are the best ways; even though it might not be a sleek one-liner, writing a plain old-fashioned for-loop is still 3 to 5 times faster than even the best LINQ version, and allocates 2 to 3 times less memory.

One-liners are not always better.

Nothing is black and white

The following piece of code (taken from the Newtonsoft.json codebase) seems, at first glance, to be ludicrous.

/// <summary>

/// Creates an array from an <see cref="IEnumerable{T}"/>.

/// </summary>

public static TSource[] ToArray<TSource>(

this IEnumerable<TSource> source)

{

IList<TSource> ilist = source as IList<TSource>;

if (ilist != null)

{

TSource[] array = new TSource[ilist.Count];

ilist.CopyTo(array, 0);

return array;

}

return source.ToList().ToArray();

}

Specifically, what is up with this?

return source.ToList().ToArray();

The overall intent of the method seems clear enough: turn an IEnumerable<T> into an array. Why not, however, just call the existing ToArray() method that is part of LINQ?

Even if there is some justification for detecting an IList<T> and hand-writing the explicit array copy code (and it is not clear at first glance that such a justification exists), why have an extraneous ToList() before calling ToArray() in the subsequent code that handles types that are not IList<T>? Is this not committing the same sin we have been arguing against? Making an entire copy of the sequence in memory just to throw it away and allocate yet another copy by copying the List into an array?

Original sequence -> copied into new List -> copied into new Array.

Garbage everywhere!

Things are not always as straightforward as they seem, however. Consider a program that uses the above extension method:

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

IEnumerable<int> list = new HashSet<int> { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 };

var array = list.ToArray(); // Calling our dubious extension method 🫤

Console.WriteLine(string.Join(", ", array));

}

public static TSource[] ToArray<TSource>(

this IEnumerable<TSource> source)

{

IList<TSource> ilist = source as IList<TSource>;

if (ilist != null)

{

TSource[] array = new TSource[ilist.Count];

ilist.CopyTo(array, 0);

return array;

}

return source.ToList().ToArray();

}

Running this program prints the following:

❯ dotnet run

1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Great, let us remove that dirty, offensive call to ToList and run it again:

// return source.ToList().ToArray();

return source.ToArray(); // Much better! 😎

Running the program again produces the following:

❯ dotnet run

Stack overflow.

Repeat 13771 times:

--------------------------------

at Program.ToArray(System.Collections.Generic.IEnumerable`1<Int32>)

at Program.Main(System.String[])

What?! Oh no! 😱

In our zealous efforts to remove an unnecessary ToList call, we introduced an incurable stack overflow bug!

What is happening here, of course, is that the ToArray that we are calling is not the one from System.Linq. It is actually the same one we just defined! If you look closely you will see that we have defined exactly the same method signature as the method from System.Linq, but because our method is in the same namespace as our class it takes precedence. This results in an infinite recursion and finally a stack overflow. 💀

In fact, it appears that this code exists in Newtonsoft.Json because it is intended to work with .NET Framework 2.0, where the Enumerable class (containing the various LINQ extension methods) did not even exist yet! It turns out that Enumerable.ToArray() does not exist in NETFX 2.0, but an explicit List<T>.ToArray() method, defined on the List<T> type itself, has existed since then. Calling ToList() here makes a ToArray() method available that will achieve the desired result without recursively stack-overflowing.

Lesson learned: even code that seems obviously wrong at first glance may be subject to subtle context that must be understood to make an informed decision about it. This is where a judicious comment explaining ‘why’ the code is the way it is can be invaluable.

Conclusion

In the bad old days of computing, so the story goes, programmers were constrained by small machines, but those days are long gone.

– Jon Bentley, Squeezing Space, Programming Pearls

As programmers in the modern world, we are awash in a glut of computer memory. Many of us hardly consider the implications of the code we write. The magic garbage collector takes care of everything and all we have to do is focus on solving the business problems at hand. You actually think saving memory, squeezing space, is a thing? Ok Grandpa, let’s get you to bed.

There was a time when computer memory was at a premium. When stepping back and thinking carefully about things like time / space tradeoffs was a critical part of the creative process of programming. When peeling back the curtain and trying, at least a little bit, to understand the implications of what is happening behind the scenes was a highly-valued skill.

In the hyperbolic title of this post, I called this the tragedy of ToList. The real tragedy, however, is the loss of awareness about these kinds of issues. Of seeing page after page of code, written by well-intentioned programmers, infested with completely unnecessary performance pitfalls due to a basic lack of critical thinking about what happens when you type those simple nine characters: .ToList().

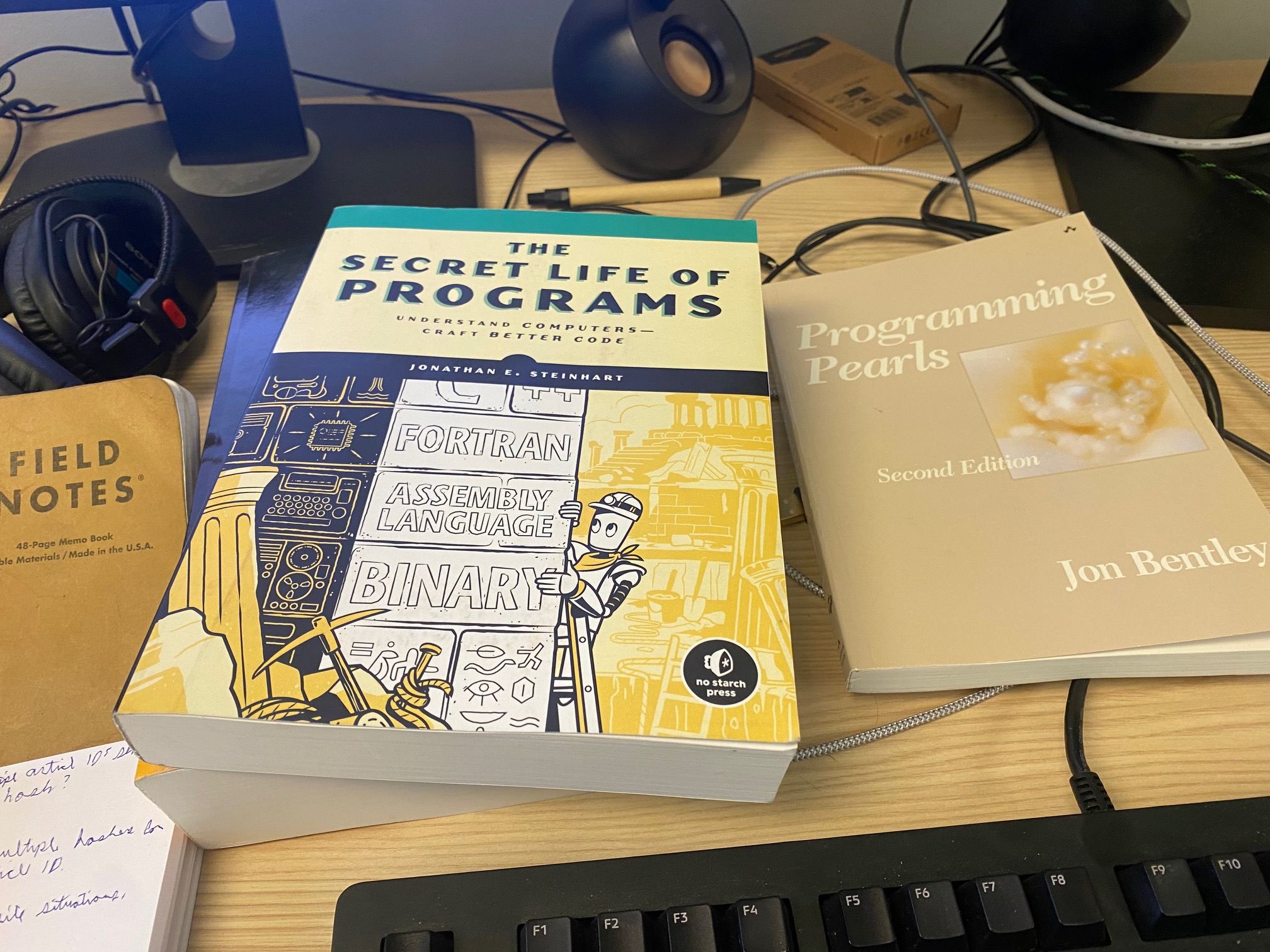

I just finished reading a book recently. It’s called The Secret Life of Programs: Understand Computers - Craft Better Code

It is an excellent book. The author is a curmudgeon in the best sense of the word, and his goal is to get newer programmers to understand not just the code they write, but how the computers that execute that code actually work. Armed with this knowledge, the individual can inform their act of writing code and create much better programs as a result.

This post is something of a small attempt to achieve the same thing. To encourage stepping back and really thinking about the code we write. Even if it is just a small and simple call to ToList() embedded in a much longer, more complex piece of code.

Nothing is ever that simple.