Converting C# projects to the new SDK format

There have been a lot of improvements to the .NET SDKs recently, driven in particular by the needs of .NET Core. Among the many changes is the newer, much lighter-weight project file syntax.

For a while there was an attempt to move project files to a JSON-based syntax (project.json), the deprecation of which seems to have been at least slightly controversial. I was lucky enough to miss most of that, as I didn’t really start working on anything outside of the full Windows-only .NET framework until the past year or so. (A bit of dabbling in running F# on Linux being a small exception.)

So, .NET project files (.csproj, .fsproj, etc.) will continue to be XML-based for the foreseeable future. However, that’s not to say there have not been some very significant improvements to the format, not the least of which are the following:

Most project items are inferred and do not need to be explicitly stated, making the project files both smaller and simpler.

PackageReference supersedes the old packages.config model for specifying your NuGet package dependencies. Both ProjectReference and the newer PackageReference are now transitive by default, meaning your project will have implicit references to the entire dependency graph, not just one-level deep. This can be both a good thing and a bad thing, but luckily the behavior can be turned on or off as needed. Here is an example of a minimal .csproj file, for a small project (project A) that has two dependencies: first on another project (Project B) and then on the System.Memory NuGet package:

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<PropertyGroup>

<TargetFramework>netstandard2.0</TargetFramework>

</PropertyGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<PackageReference Include="System.Memory" Version="4.5.2" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<ProjectReference Include="..\B\B.csproj" />

</ItemGroup>

</Project>As you can see, the new format is quite minimal and clean. Source code files are included implicitly and sensible defaults are provided for most of the many other properties that litter the more traditional, full-.NET project file syntax.

This is great if you are starting fresh and creating new projects from scratch, but what do you do if you are trying to, say, move a large existing codebase to .NET Standard and have many large, existing C# projects in the legacy format?

Luckily, Hans van Bakel has provided a nifty little tool to help with the process, and after using it to convert a few hundred projects I can attest that it really works great! I originally found out about it when a colleague pointed me to Scott Hanselman’s always-excellent blog post on the subject.

The tool can be installed as follows:

dotnet tool install --global Project2015To2017.Migrate2017.Tool(If you do not yet have a recent .NET SDK installed and the above command does not work, I would recommend going ahead and installing that first.)

If, like me, you are going to be converting many projects, I highly recommend creating yourself a little PowerShell helper function. Just add something like this to your $profile:

function conv

{

dotnet-migrate-2017 migrate $args[0]

$fldr = (Split-Path $args[0])

Remove-Item $fldr\Backup -rec -force

}In addition to saving typing, I’m assuming you are using a source control system like Git, making the backup copy created by the tool redundant. Therefore, the above wrapper script removes the backup folder.

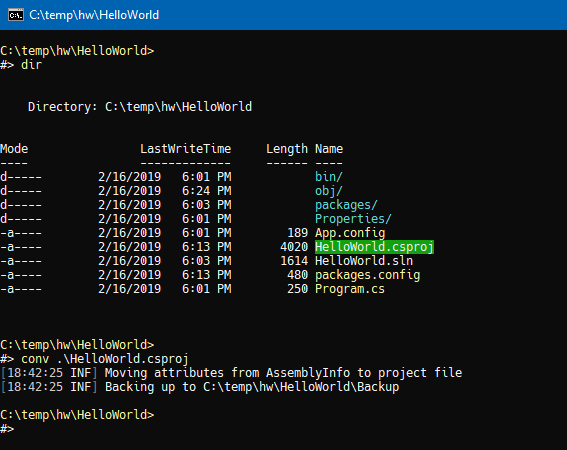

Converting a project Let’s convert a project! As an example, I’m going to use a simple HelloWorld console application that has a reference to another project and a NuGet package reference. Here it is in all of it’s ugly, traditional csproj style glory:

<Project ToolsVersion="15.0" xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/developer/msbuild/2003">

<Import Project="$(MSBuildExtensionsPath)\$(MSBuildToolsVersion)\Microsoft.Common.props" Condition="Exists('$(MSBuildExtensionsPath)\$(MSBuildToolsVersion)\Microsoft.Common.props')" />

<PropertyGroup>

<Configuration Condition=" '$(Configuration)' == '' ">Debug</Configuration>

<Platform Condition=" '$(Platform)' == '' ">AnyCPU</Platform>

<ProjectGuid>{BDC0B8D7-BEE5-417E-B5F5-3922E793C8CE}</ProjectGuid>

<OutputType>Exe</OutputType>

<RootNamespace>HelloWorld</RootNamespace>

<AssemblyName>HelloWorld</AssemblyName>

<TargetFrameworkVersion>v4.7.2</TargetFrameworkVersion>

<FileAlignment>512</FileAlignment>

<AutoGenerateBindingRedirects>true</AutoGenerateBindingRedirects>

<Deterministic>true</Deterministic>

</PropertyGroup>

<PropertyGroup Condition=" '$(Configuration)|$(Platform)' == 'Debug|AnyCPU' ">

<PlatformTarget>AnyCPU</PlatformTarget>

<DebugSymbols>true</DebugSymbols>

<DebugType>full</DebugType>

<Optimize>false</Optimize>

<OutputPath>bin\Debug\</OutputPath>

<DefineConstants>DEBUG;TRACE</DefineConstants>

<ErrorReport>prompt</ErrorReport>

<WarningLevel>4</WarningLevel>

</PropertyGroup>

<PropertyGroup Condition=" '$(Configuration)|$(Platform)' == 'Release|AnyCPU' ">

<PlatformTarget>AnyCPU</PlatformTarget>

<DebugType>pdbonly</DebugType>

<Optimize>true</Optimize>

<OutputPath>bin\Release\</OutputPath>

<DefineConstants>TRACE</DefineConstants>

<ErrorReport>prompt</ErrorReport>

<WarningLevel>4</WarningLevel>

</PropertyGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<Reference Include="System" />

<Reference Include="System.Buffers, Version=4.0.2.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=cc7b13ffcd2ddd51, processorArchitecture=MSIL">

<HintPath>packages\System.Buffers.4.4.0\lib\netstandard2.0\System.Buffers.dll</HintPath>

</Reference>

<Reference Include="System.Core" />

<Reference Include="System.Memory, Version=4.0.1.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=cc7b13ffcd2ddd51, processorArchitecture=MSIL">

<HintPath>packages\System.Memory.4.5.2\lib\netstandard2.0\System.Memory.dll</HintPath>

</Reference>

<Reference Include="System.Numerics" />

<Reference Include="System.Numerics.Vectors, Version=4.1.3.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=b03f5f7f11d50a3a, processorArchitecture=MSIL">

<HintPath>packages\System.Numerics.Vectors.4.4.0\lib\net46\System.Numerics.Vectors.dll</HintPath>

</Reference>

<Reference Include="System.Runtime.CompilerServices.Unsafe, Version=4.0.4.1, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=b03f5f7f11d50a3a, processorArchitecture=MSIL">

<HintPath>packages\System.Runtime.CompilerServices.Unsafe.4.5.2\lib\netstandard2.0\System.Runtime.CompilerServices.Unsafe.dll</HintPath>

</Reference>

<Reference Include="System.Xml.Linq" />

<Reference Include="System.Data.DataSetExtensions" />

<Reference Include="Microsoft.CSharp" />

<Reference Include="System.Data" />

<Reference Include="System.Net.Http" />

<Reference Include="System.Xml" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<Compile Include="Program.cs" />

<Compile Include="Properties\AssemblyInfo.cs" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<None Include="App.config" />

<None Include="packages.config" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<ProjectReference Include="..\SampleLibrary\SampleLibrary.csproj">

<Project>{99e7fcdd-9bab-457c-ad10-65a11dea2d33}</Project>

<Name>SampleLibrary</Name>

</ProjectReference>

</ItemGroup>

<Import Project="$(MSBuildToolsPath)\Microsoft.CSharp.targets" />

</Project>Using our helper PowerShell function, we can simply change to the folder where the project lives, run conv HelloWorld.csprojand the tool will do all of the heavy lifting.

After running the conversion, we get the following result:

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<PropertyGroup>

<ProjectGuid>{BDC0B8D7-BEE5-417E-B5F5-3922E793C8CE}</ProjectGuid>

<OutputType>Exe</OutputType>

<TargetFramework>net472</TargetFramework>

<AutoGenerateBindingRedirects>true</AutoGenerateBindingRedirects>

<GenerateAssemblyInfo>false</GenerateAssemblyInfo>

<OutputPath>bin\$(Configuration)\</OutputPath>

</PropertyGroup>

<PropertyGroup Condition=" '$(Configuration)|$(Platform)' == 'Debug|AnyCPU' ">

<DebugType>full</DebugType>

</PropertyGroup>

<PropertyGroup Condition=" '$(Configuration)|$(Platform)' == 'Release|AnyCPU' ">

<DebugType>pdbonly</DebugType>

</PropertyGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<PackageReference Include="Newtonsoft.Json" Version="11.0.1" />

<PackageReference Include="System.Buffers" Version="4.4.0" />

<PackageReference Include="System.Memory" Version="4.5.2" />

<PackageReference Include="System.Numerics.Vectors" Version="4.4.0" />

<PackageReference Include="System.Runtime.CompilerServices.Unsafe" Version="4.5.2" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<Reference Include="Newtonsoft.Json, Version=11.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=30ad4fe6b2a6aeed, processorArchitecture=MSIL">

<HintPath>packages\Newtonsoft.Json.11.0.1\lib\net45\Newtonsoft.Json.dll</HintPath>

</Reference>

<Reference Include="System.Buffers, Version=4.0.2.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=cc7b13ffcd2ddd51, processorArchitecture=MSIL">

<HintPath>packages\System.Buffers.4.4.0\lib\netstandard2.0\System.Buffers.dll</HintPath>

</Reference>

<Reference Include="System.Memory, Version=4.0.1.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=cc7b13ffcd2ddd51, processorArchitecture=MSIL">

<HintPath>packages\System.Memory.4.5.2\lib\netstandard2.0\System.Memory.dll</HintPath>

</Reference>

<Reference Include="System.Numerics.Vectors, Version=4.1.3.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=b03f5f7f11d50a3a, processorArchitecture=MSIL">

<HintPath>packages\System.Numerics.Vectors.4.4.0\lib\net46\System.Numerics.Vectors.dll</HintPath>

</Reference>

<Reference Include="System.Runtime.CompilerServices.Unsafe, Version=4.0.4.1, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=b03f5f7f11d50a3a, processorArchitecture=MSIL">

<HintPath>packages\System.Runtime.CompilerServices.Unsafe.4.5.2\lib\netstandard2.0\System.Runtime.CompilerServices.Unsafe.dll</HintPath>

</Reference>

<Reference Include="System.Data.DataSetExtensions" />

<Reference Include="Microsoft.CSharp" />

<Reference Include="System.Net.Http" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<ProjectReference Include="..\SampleLibrary\SampleLibrary.csproj" />

</ItemGroup>

</Project>The tool did quite a bit of work for us, including converting the NuGet references to PackageReference (the packages.config was also deleted), removing any source-code file references (since they will be implicitly included) and removing other extraneous properties.

It’s not perfect, however. You will notice there are still references with hint paths to some files under the packages folder. These really should have been removed, as those entries are replaced by the PackageReference items. In addition, the explicit reference entries to things like Microsoft.CSharp are not necessary and can be removed, as can items like ProjectGuid, which as far as I know serves no useful purpose.

However, once you recognize what can be safely removed, it takes just a couple of seconds in your favorite text editor to elide the remaining cruft and be left with something quite nice, like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<PropertyGroup>

<OutputType>Exe</OutputType>

<TargetFramework>net472</TargetFramework>

<AutoGenerateBindingRedirects>true</AutoGenerateBindingRedirects>

<GenerateAssemblyInfo>false</GenerateAssemblyInfo>

<OutputPath>bin\$(Configuration)\</OutputPath>

</PropertyGroup>

<PropertyGroup Condition=" '$(Configuration)|$(Platform)' == 'Debug|AnyCPU' ">

<DebugType>full</DebugType>

</PropertyGroup>

<PropertyGroup Condition=" '$(Configuration)|$(Platform)' == 'Release|AnyCPU' ">

<DebugType>pdbonly</DebugType>

</PropertyGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<PackageReference Include="Newtonsoft.Json" Version="11.0.1" />

<PackageReference Include="System.Buffers" Version="4.4.0" />

<PackageReference Include="System.Memory" Version="4.5.2" />

<PackageReference Include="System.Numerics.Vectors" Version="4.4.0" />

<PackageReference Include="System.Runtime.CompilerServices.Unsafe" Version="4.5.2" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<ProjectReference Include="..\SampleLibrary\SampleLibrary.csproj" />

</ItemGroup>

</Project>There you have it! A traditional C# project converted to the new format.

This was a fairly trivial example, but even on large projects with tens of thousands of lines of code and custom build targets and other complexities, my experience is that this process will get you almost all the way there, with only a few small tweaks needed to complete the process.

Of course, actually converting to something like .NET Standard once you have switched over to the new SDK project format is an entirely different can-of-worms.